Does Your Customer’s Car Have a Drug Problem?

When your customer’s vehicle is stolen and police recover it, what’s the first thing they will probably want to do after it is returned? Open the doors, pop the trunk, and look around inside, right?

That may be the same thing you and your employees do when that customer pulls the vehicle into your body shop for repairs. But beware. Theft- recovery vehicles can be toxic with highly dangerous and potentially life-threatening levels of drug residue.

The Backstory

According to a September 2023 New York Post report, when a family in Washington state got back their stolen 2002 Ford F150 pickup, it appeared to be in pristine condition. So the owner, a father of a five- and 10-year-old, took a drive with his kids.

Shortly after, the stomach aches and headaches started.

Collision industry executive Erin Solis, senior vice president of Reno, Nevada,-based Square One Systems, is working diligently to tell this story and drive home the seriousness of the situation. Her goal is to raise awareness and save lives in the process. And since Square One Systems manages “20 groups” with the Coyote Vision Group, with about 100 shops in various locations, she’s got a good start.

“I did a presentation with Coyote Vision Group at the start of the year,” Solis says. “I shared many stats, and although there’s no adequate tracking of these cases currently, we tried to track [ourselves].”

Out of 23 theft-recovery vehicles that Square One Systems inspected, 83% showed detectable levels of methamphetamine, while 30% had detectable levels of fentanyl.

“People are oftentimes not thinking about this,” Solis emphasizes.

The Challenge

Rob Grieve, owner of Nylund’s Collision Center in Englewood, Colorado, is in alignment with Solis. So much so, he mandates drug testing of every theft-recovery vehicle that rolls inside his shop.

It’s a standard procedure he put into place that helps prevent potential drug exposures like the one he averted with a Hyundai Tucson the Denver Police Department recovered in October 2023. Before letting his team touch the vehicle, on which the windows had been spray-painted black, Grieve called in The Vertex Cos. LLC, a Colorado company that provides drug testing and analysis.

From visual examination, Vertex’s professionals spotted a glass pipe and methamphetamine paraphernalia. Next, from wipe samples they obtained and sent to a lab, they confirmed surface drug concentrations high enough to meet the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s threshold that mandates complete decontamination or demolition.

While this particular theft-recovery vehicle provided visual clues that drug material was present, some vehicles don’t show any sign of it. “You can’t see what’s really going on unless there’s drug paraphernalia left behind,” Grieve says. “A couple of grains of fentanyl can make people incredibly sick and even kill them, though.”

The Solution

The only safe way for collision repair shops to test and clean customers’ theft-recovery vehicles is to hire a professional company, Grieve says. He cautions anyone who would try to buy a test off Amazon and do the job of testing and cleaning themselves.

In vehicles with drug contamination levels low enough that they can be cleaned and used again, Grieve says there are special ways that licensed technicians clean them.

“An industrial hygienist puts all the samples in individual containers [labeled] with the location of where they came from [in the car],” Grieve describes. “All these are sent to a lab that reports back on each sample. There’s a standard for meth, [for instance], with a certain number of particles, and if the testing shows it’s below, it can be cleaned.”

Even after cleaning, however, a vehicle must be tested again — with samples sent back to the lab for testing and a wait time to learn the results — before anyone can safely touch it to begin repairs and body work.

“It becomes cost-prohibitive,” Grieve admits. “Cleaning by a certified person is expensive, and the drug tests [can run] around $1,400 for each one, and that’s before you’ve even gotten to the vehicle’s damage.”

Tamping down the solution even further, customers’ insurance companies often balk at paying for the testing, Grieve has found.

The Aftermath

Although the main reason Grieve began testing theft-recoveries in the first place is the safety of his employees, he now works to educate his customers on the front end.

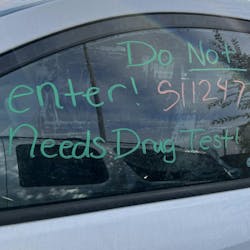

“We advise that the customer doesn’t enter a recovered vehicle until we know it’s safe. They should tow it [to us] and not drop it off,” Grieve says. “Then we seal it and nobody enters it until a drug test is completed.”

He adds, “There’s more than drug residue [to worry about]; needles can be between the seats.”

Ever working to shine a light on the problem of drugs in vehicle theft and recovery scenarios, Solis reminds shop owners, technicians, and car owners that the level of danger a car poses is invisible until a professional test uncovers the actual chemistry behind the contamination.

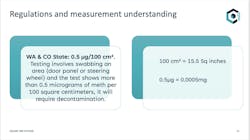

Using methamphetamine as an example, Solis says that in the states of Washington and Colorado, if swab tests taken from steering wheels and door panels indicate more than 0.5 micrograms of meth per 100 square centimeters, the vehicle will require decontamination before it’s safe to enter.

To illustrate just how much danger can truly exist in theft and recovery scenarios, Grieve drives home this point: “With the drug company we use [for testing vehicles], they always have two people – one inside the vehicle and one outside – and they’re both [hazmat] suited up with respirators and everything,”

Then he adds, “The one outside the car stands there with Narcan in case the guy inside the car collapses. It’s a very serious deal.”

About the Author

Carol Badaracco Padgett

Carol Badaracco Padgett is an Atlanta-based writer and FenderBender freelance contributor who covers the automotive industry, film and television, architectural design, and other topics for media outlets nationwide. A FOLIO: Eddie Award-winning editor, writer, and copywriter, she is a graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism and holds a Master of Arts in communication from Mizzou’s College of Arts & Science.