YesterWreck – The Column #4: The Collision Repair Industry in the 1920s

Editor's Note: This is the fourth in a series, excerpted from Ledoux’s book, YesterWreck: The History of the Collision Repair Industry in America available here.

In 1920, there were over 106,000,000 Americans. Some were able to experience the first talking films in 1923, but most were not able to enjoy their favorite “hard” drink, as liquor was prohibited by the Volstead Act. In 1924, IBM was founded, starting a new world of business machines, and later, computers. Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic and faces began to appear on Mount Rushmore. In 1927, Philo Farnsworth invents the first practical television. (What would he think of the ubiquitous video screens used in the cars of the early 21st century?) By the end of 1929 it seemed like America — and most of the world — was falling apart with the collapse of the stock market.

The Expansion of the Automobile

The decade of the ‘20s saw an expansion of the automobile and where it was driven. Early in the decade, auto manufacturers were afraid that the auto industry had reached “optimum saturation.” It was thought that that everyone who could or wanted to buy a car had bought one and that sales would be reduced to a trickle. This changed their advertising tactics. Rather than promote the automobile as a “pleasure car”, they would now promote it as a “necessity of the modern age.” The ploy apparently worked. Soon, it was plain that the automobile would claim the roads from horses and carriages. But that created a problem for most cities. Their main streets were too narrow for the growing number of cars, making the downtown shopping experience less than pleasurable.

It was said that the problem was not the automobile, but the government’s inability to provide adequate infrastructure for the new travel media. Some cities asked local car dealers to pitch in and build parking structures in the downtown area. Some wanted a pedestrian downtown area, while forcing car owners to shop in yet-to-be-built suburban shopping malls. By 1927, traffic in some cities had become untenable with “an alarming number of deaths due to automobile accidents.”

With the advent of suburban shopping areas, car manufacturers started marketing to women, who would use the family car during the week to go shop outside town. There were more roads, more vehicles, more vehicle miles traveled, more accidents, and more need for collision repair... and more need to adapt collision repair to newer, more sophisticated body styles.

The Expansion of Automotive Color

With the end of WWI, and the development by American chemical companies of various synthetic dyes making colored consumer products more available, American industry was investing in color management. Henry Ford’s idea of only black cars was quickly becoming dated. The days of black and white were numbered.

Industrial scientists of the day concerned themselves with “why” light behaved as it did to create the spectrum of color. Aesthetic theorists wondered “how” colors made people behave in certain ways and how color acquired certain cultural meanings. Functional colorists, more specifically, those charged with deciding what color to apply to what object, wanted to know what color people preferred for such things as a car.

In the 1920s, and even today, those who labor in the art and science of color work mostly in anonymity, unknown to vehicle owners, body refinishers, and even those working in the car factories. But their work is out there for the world to see, and for refinishers to duplicate.

Many in the auto industry know the name of Harley Earl, the iconic General Motors car designer responsible for the “finned” look of the 1950s automobiles. But practically nobody has ever heard of H. Ledyard Towle, a genius in his own right who had an office right next to Harley Earl. Earl decided how big the fins should be on a GM car, and Towle decided what color to paint them. Towle, and others like him who worked for the U.S. government creating camouflage paint jobs for jeeps and tanks and boats during the war years, were now in charge of deciding which two-tone paint job would look best on the latest sedan.

Automakers began to realize that more color would sell more cars, but they needed a way to paint cars more efficiently with a quality, more durable coating that would not crack, craze, peel or fade in a short time. The search was on for just such a product.

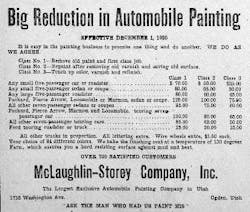

In 1924, DuPont introduced Duco nitrocellulose lacquer, the first sprayable automotive paint. (It had to be sprayed; it dried too fast to be brushed!) Its solvent-evaporation drying process reduced painting time from 30 days to two hours, greatly enhancing new-vehicle production and allowing a myriad of colors. The first car painted with Duco lacquer was the 1924 Oakland, a medium blue, and purportedly sprayed with a DeVilbiss spray gun.

The Expansion of Paint Application Technology

The expansion of color and color application happened at about the same time. By the mid-1920s, DeVilbiss, Binks, and Iwata were in the spray gun business, and nitrocellulose paint was ready to be sprayed. The only problem was the overspray went everywhere – including into the lungs of the refinisher.

And then, you might say hamburgers rescued the collision repair industry. Air exhaust technology was borrowed from the food preparation industry in the form of updraft booths. The exhaust hoods that pulled greasy fumes from frying burgers were enlarged and placed in a crude booth. This was better than an open window, but it proved inadequate. Some painters experimented by placing a fan in an open window to suck out the heavy paint particulates. But this led to another problem. Sticky paint particles sticking to the fan blades, over time and many paint jobs, made them very inefficient. Then, some innovative painter figured out if he put vertical wooden slats in front of the fan blade, the paint would stick to the slats and not the blade. To make it work even better, another set of slats was added in an offset manner so even more overspray could be collected. Painters even greased the slats to make removal of overspray easier, but it was still not a foolproof system. Eventually, spray gun makers found it to their best advantage to get into the spray booth-building business. One product supported the other.

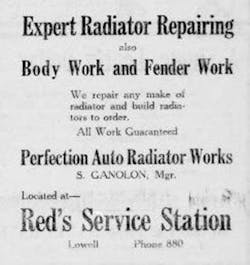

The Expansion of the Automotive Repair Industry

By the early to mid-1920s, a change began to happen in the world of auto repair. The car began to get more sophisticated. Repair of engines and other systems still required the visceral knowledge of the current-day mechanics or “garage-men” or “repairman” as they were called, men (usually men) who could simply listen to a running automobile and know if it was running “right”…or not. But a subspecialty began to emerge, those specializing in electrical work. There is also evidence that this period ushered in those shops that specialized first in auto painting, because a car’s original paint job was not very durable, and then collision repair.

Some shops even went into the body-building business. The January 1920 issue of Blacksmith and Wheelwright magazine suggested that blacksmiths use the “slow time” during the winter to build what amounted to a 1920s version of an airport/hotel transit bus capable of carrying a number of passengers and all their luggage from train station to their hotel.

Thus, with the ability to repair or build certain metal parts, the ability to weld, and the ability to work with wood and paint, many, but not all, blacksmith shops became the first auto repair shop and de facto body shops. The blacksmith shops of the late 1910s and early 1920s had emerged from the single forge and one-anvil operation that mainly shod horses and repaired wagons, to an intricate array of tools and machinery which made the blacksmith shop more like a machine shop.

The transition from blacksmith to auto repair was urged by many of the blacksmith’s trade journals. As early as January 1900, Blacksmith and Wheelwright magazine predicted that as soon as automobiles came into general use, the blacksmith would be called upon for repairs. Ironically, carriage-makers felt differently, that they should be the ones making repairs since the automobile bodies were made of wood.

By the mid to late 1920s, the industry was changing again. The auto dealership was emerging as a force in the industry. So, too, were auto repair shops opening expressly for the purpose of auto and body repair. Those blacksmiths who had the vision to see the future went into the auto repair/body and painting business and gradually phased out their traditional blacksmithing business. Some blacksmiths simply retired. And some rode the business to its eventual demise in the 1930s.

As might be expected in those blacksmith shops run by first-generation proprietors, it was the second generation, usually a son, who brought the shop into the auto age. There is indication that early mechanics were, in fact, younger people, who embraced the new technology, and could see the future coming at them… with increasing speed.

This is the fourth in a series, excerpted from Ledoux’s book, YesterWreck: The History of the Collision Repair Industry in America available here.

Part 1 of YesterWreck, the Column

About the Author

Gary Ledoux

A native of New Hampshire, Gary Ledoux retired in 2017 after a 48-year career in the automotive industry. For 18 years, he worked in various capacities in numerous car dealerships in New Hampshire. In 1988, Gary began his career with American Honda, eventually serving as the assistant national manager for American Honda’s Collision Parts Marketing Department, and was instrumental in launching Honda’s certified body shop program. He was very active in the collision repair industry, serving on various Collision Industry Conference (CIC) committees and as a three-time chairman of the OEM Collision Repair Roundtable. Today, Ledoux is a freelance writer splitting his time between his Florida home and vacation property in South Carolina. In the summer of 2018, he published his fifth book, YesterWreck: The History of the Collision Repair Industry in America.